1960

November 25, 2020

This section mentions slaves and murder.

1961

Freshman initiation week.

According to “College of Our Dreams,” Freshman Initiation Week signified the induction of the “hapless first-year students. The sophomore class required the ‘Frosh’ to paint ‘CLC’ on the rocks on the side of Mt. Clef, to be subject to a Kangaroo Court, and to gather at a grand bonfire finale. Although heavy rains and fierce winds forced them to cancel the latter event the first year, a ‘sizeable share of fun-tainted misery’ was dished out to the freshman who were required to wear purple and gold beanies, bibs with their names inscribed on them, and to perform certain chores.”

The first residential students arrive.

When the students moved in, the dorms weren’t quite ready, Karsten Lundring, class of ‘65 alumnus said in a Zoom interview on Oct. 14, 2020. “They didn’t have the doors on the rooms. The showers weren’t working, other than that the rooms were there… it was like three or four days before the showers and the front doors were put on the apartments–we were pioneers.”

According to the 2018 Cal Lutheran Presidential Host Handbook, Thompson and Pederson, originally Alpha and Beta, “were designed with the courtyard in the middle so if the school went bankrupt, they could be easily converted into hotel rooms.”

1962

February 22: Cal Lutheran College receives accreditation.

Cal Lutheran President Orville Dahl returned from a meeting in Los Angeles with the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) and announced Cal Lutheran was accredited as a senior liberal arts college.

“We have that Echo [newspaper] that says accredited on [the front] with letters [all] big–and man that was a huge deal,” Lundring said. “We had this big celebration out between Alpha and Beta or Thompson/Pederson and he brought this report back saying we’re accredited, and I mean, I don’t know if you can imagine the excitement of hearing this, because we all came to an unaccredited school.”

1963

August 28: Students call on religious leaders for a conversation about integrating the Lutheran Church.

According to “College of Our Dreams,” “after the famous ‘I Have a Dream’ speech by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. students at CLC called upon the Rev. Lee Wesley of Immanuel Lutheran Church, Los Angeles, to lead a three-day retreat on ‘The Church and Integration.’”

1964

March: Wesley R. Brazire, executive director of the Los Angeles Urban League, speaks at Cal Lutheran.

“Wesley R. Brazire, Executive Director of the Los Angeles Urban League, also spoke at a special convocation in March 1964, in which he recounted his personal experiences in the ‘battle for human rights,’’ according to “College of our Dreams.”

May: Cal Lutheran holds its first commencement ceremony.

1965

New freshman initiation ceremony.

According to Maria C. Grago, alumna class of ’69, in “I remember CLC/CLU”, freshman initiation ceremonies included asking freshman to “bend over and touch your beanie and recite ‘I a lowly Freshman salute you almighty Sophomore.”

Faculty members are no longer required to attend convocations and chapel–but students still are, according to “College of our Dreams.”

Cal Lutheran Student Council sent a student to be an eyewitness to the Civil Rights marches in Alabama.

Student Council President George Engdahl and Senior Class President Bill Ewing raised $350 in donations from students, faculty and community members to send Jerry Radke, a 21-year-old pre-medical student, as an impartial observer of the events in Selma and Montgomery, Alabama.

“I had these memories… that came and they were absolutely clear to me about when I was on Student Council in 1965. And we as a Student Council decided to send someone down to march… and he did come back and give a report,” Lundring said.

Lundring said the council would have sent an African American student, but there were less than five on campus.

“We probably had what, Lonnie Anderson? I can remember the name, that’s how few [Black students] we had… we were not integrated,” Lundring said. “It was a very very white campus.”

“The race thing isn’t new. You know, it was a big deal then [and] it unfortunately still is.”

March: A ‘Minstrel show’ is proposed.

California Lutheran College Letterman’s Club began rehearsing for a ‘minstrel show,’ “a popular type of entertainment that had originated in the 1830s where white men dressed up as a parody of plantation slaves,” according to “College of Our Dreams.”

“When it was learned that such a performance was planned, two CLC students, Dave Anderson, whose father was active in civil rights groups, and Elwin Josephson, led protests against it, arguing before the Student Council that ‘the shows, if permitted, would be downgrading the cause of civil rights.’ The council then advised the club to have a variety show instead,” the book states.

Only three Black students were enrolled at CLC at the time.

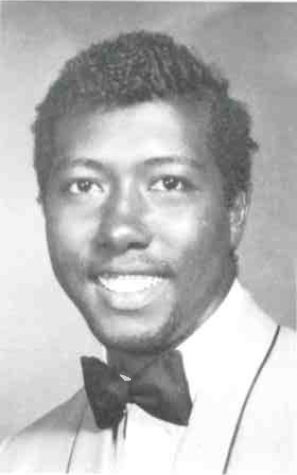

According to Lundring and class of ‘69 alumna and Professor of Psychology Julie Kuehnel, these few Black students included ‘Lonnie’ Anderson and Willie ‘Jim’ Ware. Ware went on to become a Superior Court Judge.

1967

Feb. 20: Cal Lutheran students protest campus closures during chapel hour and gain library access.

According to “College of Our Dreams,” 200 students participated in a “silent sit-down strike by two hundred students outside the gymnasium during the chapel service and a letter to the president of the school on February 20, 1967, was effective in ending” required chapel attendance.

“We objected to them closing the library during chapel, because we were like what is this a church? or, you know… so a whole bunch of us got together and we marched up to the president’s office and he was having a cabinet meeting and we marched into the cabinet meeting. And, like, you know, yelled about that and everything, so we did that,” Kuehnel said.

Michaela Reaves, class of ‘79 alumna and professor of History, said at that time Cal Lutheran closed everything during chapel.

“As a commuter with no car I had nowhere to go so I asked that something stay open so commuters like me had a place to go out of the rain,” Reaves said in an email interview on Nov. 11, 2020.

May 1: First “Yam Yad” is celebrated.

“That was May Day backwards. And our class is the one that started it and it was a great thing. It was like a surprise to everybody. Nobody knew that it was coming, they woke everybody else with music at like 6:30 in the morning they ran through the dorms and classes were canceled,” Kuehnel said.

Yam Yad was a day full of non-academic fun.

“We went out to Paramount Ranch and they had games contests and all kinds of things and then in the evening they had a hypnotist come and entertain us–all this kind of stuff,” Kuehnel said. “And it was really meant to be community building, you know, and it did, you know, it was very community building.”

1968

Women had strict curfew hours while men did not.

The women’s dorms had a curfew of 10 p.m. on weekdays and midnight on weekends, but the “boys’ dorms did not,” Kuehnel said. “So it was a really a sexist thing and we objected to it but we never really got very far.”

According to Karen Ingram, alumna class of ’74 in “I remember CLC/CLU” the women residents had a sit-in in their PJs “some with hair in curlers, filled the Mt. Clef foyer. We spent the night singing, playing board games and getting to know each other. I don’t remember sleeping, but I’m sure we did.”

The curfew was abolished the next year, according to “I remember CLC/CLU.”

April 4: Students react to Martin Luther King assassination.

“When Martin Luther King was shot… that was a big thing. We had a big [protest] and marched down Moorpark [road], you know on the median and everything like that, and it was that was a real big deal. We were very much an activist group,” Kuehnel said. “We were all pretty politically active at that time.”

According to “College of Our Dreams” the students asked President Ray Olson to speak. “At the end [of the procession], there were not only students but also people from the churches and the community, and still others who opposed the march so intensely that they were ready to ‘gun me down,’ according to Olson. Noting how agitated everyone was, he carefully begged the audience to consider the complex tasks facing the governing authorities. Olson’s strategy was to step back from the confrontation and ‘take a sober look at what was taking place,’ and try to resolve it.”