Reporting Processes, Title IX at Cal Lutheran: Three Women’s Stories

On California Lutheran University’s “Sexual Misconduct and Title IX” webpage, sexual misconduct is presented as a serious violation of the university’s mission.

“Sexual misconduct violates the values of our community as well as the University’s mission to educate leaders who are strong in character and in their identity and vocation, and committed to service and justice,” the website states.

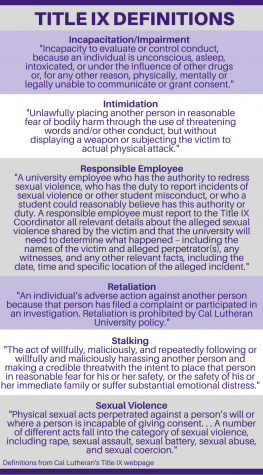

Title IX, a section of the Education Amendments of 1972, prohibits discrimination based on sex in education programs and activities in federally funded schools at all levels, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Sex discrimination includes sexual assault, harassment, domestic violence and stalking, according to Cal Lutheran’s website.

In three cases, students and a former student shared concerns about the university’s handling of Title IX-related matters, including rape, assault and “stalker behavior.”

Title IX Coordinator Jim McHugh and Deputy Title IX Coordinator Chris Paul were asked by The Echo to discuss specific cases. In a Nov. 16 email, McHugh informed The Echo that “we will not discuss the handling of any case. All case [sic] are handled according to the Title IX procedures in place at the time the incident is reported.”

Allison

In September 2017, a student at Cal Lutheran, who was a sophomore at the time, filed a Title IX report that included allegations of rape against three other students. The student, who will be referred to by the pseudonym Allison, has since transferred. Allison said the three alleged perpetrators, all of whom were student athletes, engaged in sexual acts with her on Sept. 10, 2016 while she was too incapacitated to consent.

“I wasn’t going to report it for a long time because I was dealing with a lot of [post-traumatic stress disorder], because they sexually assaulted me and all that, and there was a lot of victim shaming from people, and people not believing me,” Allison said.

Allison’s first-year roommate, a current senior at Cal Lutheran who will be referred to by the pseudonym McKenna, said Allison went out the night of the alleged assault and “didn’t come home with everyone else.” When she came home, she seemed “shut down a little bit,” McKenna said. McKenna said Allison later told her she’d been assaulted.

Allison said she decided to report the incident to Residence Life when she returned for her sophomore year.

Allison’s case was assigned by Paul to Senior Coordinator for Residence Life and Student Conduct Andy Hanson for review. Allison said Hanson was understanding during their first meeting, which took place on Sept. 21, 2017, according to her Title IX investigation report.

“Then I went in for my second interview with the investigator, and this is after he had talked to the three boys who had assaulted me, and his demeanor was completely different. He was … almost abrasive,” Allison said.

According to the investigation report, her second meeting with Hanson took place on Nov. 29, 2017, and followed meetings with a witness, the three accused students and two of the accused students’ lawyer. McKenna, a second witness listed in the report, was interviewed by Hanson on Dec. 1, 2017.

On March 12, 2018—more than 180 days after Allison filed a complaint—the 28-page investigation report was completed to be sent to McHugh for review and shared with Allison via Dropbox.

Prior to September 2017, Title IX investigations had to be completed within 60 days, according to Attorney Joseph Lento, who specializes in Title IX law. However, on Sept. 22, 2017, the U.S. Department of Education withdrew the 60-day timeframe.

The report concluded that “using a preponderance of the evidence standard”— meaning more likely than not—Hanson found it “undisputed” that two of the accused students engaged in oral penetration and one accused student engaged in vaginal penetration with Allison in Potenberg Hall.

“The question is then whether Allison had capacity to consent to any of the sexual activity. Based on the information gathered from the individual reports, the undisputed facts, the resolution of the disputed facts as set forth above, I find that Allison was intoxicated to the point of incapacity to affirmatively consent, and [the alleged perpetrators] should have known of Allison’s incapacitation,” Hanson wrote at the conclusion of the investigation report.

However, on April 26, 2018—following over a month where Allison said she heard nothing about the report—Allison received a letter from McHugh via an email from Paul stating that the three alleged perpetrators had been “found not responsible for a Title IX policy violation following the Title IX investigation.”

“I was shocked, because the report had a completely different conclusion,” Allison said.

Cal Lutheran’s Title IX procedures are outlined in the “Title IX and Clery Amendments Policy.” This policy states “At the conclusion of the investigation, the Investigating Officer will make a decision regarding any findings of responsibility and present it to the Title IX Coordinator to issue any consequent disciplinary sanctions.”

“As per our process, both the reporting party and responding parties must be informed of the outcome of the factual findings, determination of responsibility, and any sanctions affecting the reporting party within three (3) business days of the Hearing Officer’s decision,” McHugh’s letter to Allison stated.

The Echo asked McHugh and Paul to clarify the role of a hearing officer. In a Nov. 16 email, they responded stating “there is no hearing officer.”

Allison said she responded to Paul by copying and pasting the conclusion from the investigation report. Allison said she had downloaded the report when it was first shared with her, and after she had already downloaded it she was told by Paul not to.

“I am concerned that you have downloaded the file that I shared with you on Dropbox or copied it in some way. We were able to get you the report however, you should not have a copy of it,” Paul stated in an email on May 4, 2018.

S. Daniel Carter, a Clery Act expert and campus security consultant, said a website called Box is more commonly used by universities to share documents as it allows for a higher degree of control.

Cal Lutheran’s Title IX policy does not address the right of students to retain their report, although Cal Lutheran’s 2019-2020 Student Handbook discusses the right to review it, stating that reporting and responding parties will have the opportunity to review a report summarizing all factual evidence in advance of the decision of responsibility.

Additionally, the U.S. Department of Education’s September 2017 “Q&A on Campus Sexual Misconduct,” which is used to assess a school’s compliance with Title IX, states that “The decision-maker(s) must offer each party the same meaningful access to any information that will be used during informal and formal disciplinary meetings and hearings, including the investigation report.”

Carter said the Department of Education has not yet addressed “what exactly access means,” but it has not yet been interpreted as the right to retain information.

Allison said she asked Paul what happened to change the conclusion, and was sent an amended analysis “created after responses were received from the responding parties,” according to Paul’s email.

The amended analysis stated that Allison had tampered with text message evidence, and mentioned the testimony of the accused students who said that Allison did not show signs of intoxication.

“The consistency of the testimony by responding parties of [Allison] not stumbling, not showing signs of intoxication at all, weighed with the new assessment of credibility per the new evidence, causes me to reevaluate whether I find [Allison] had capacity to consent and in fact affirmatively consented,” the amended analysis stated.

Allison said she showed her investigator all the messages she was in possession of, “including messages that did not look great for me.” Another witness had testified as to her intoxication in the investigation report. Text message evidence in the original investigation report included texts sent to one of the alleged perpetrators by Allison the morning after the alleged assault stating, “I remember close to nothing.”

In 2014, California became the first state to pass a law stating that consent could not be given when “the complainant was incapacitated due to the influence of drugs, alcohol, or medication,” and that consent must be “ongoing throughout a sexual activity.”

Allison said she was never sent the revised investigation report containing new evidence referenced in the amended analysis.

“Both the complainant and respondent are entitled to all information to be used during any proceeding. So the responses to the investigatory report, before it was final, are part of that information used in the proceeding. The complainant should have been privy to that information,” Carter said.

McHugh’s letter stated that the request for an appeal would only be granted if new information became available or if the process as outlined in the Student Handbook was not followed throughout the investigation.

“I couldn’t do anything because I didn’t know what information I would be appealing,” Allison said.

Carter said the Clery Act “absolutely requires” all information used in a proceeding to be provided to both parties, and “not after the fact.”

“So, it could not have been tacked on to the finding. Although that would perhaps enabled the complainant to understand whether or not they have a basis to appeal,” Carter said.

Allison said she did not fight the case further because she was out of the “triggering situation.”

“I had moved on with my life at that point, that I decided it wasn’t worth the time and energy to find a lawyer, to do anything like that,” Allison said.

Allison said the incident and the way her case was handled was one of the main reasons why she chose to transfer.

“I was appalled with how they handled it… it blew my mind,” Allison said. “It’s funny because now I go to [another university in an area] where there’s a lot of crime… I feel safer on this campus than I did at Cal Lu.”

Her former roommate McKenna said the case seemed to go by very fast, and although she said it was difficult as the report was filed a year after the alleged incident, she wished that the investigation had gone further.

“I wish she had gotten better justice than she had, than she did,” McKenna said.

The three alleged perpetrators continued their education at Cal Lutheran and have since graduated.

Shannon

Several weeks into her first year of college in fall 2016, Shannon, now a senior at Cal Lutheran, said she was awoken at 3 a.m. on a Sunday to a shirtless man touching her in her sleep. She said this man was in her dorm room in South Hall two times that night.

“One night, my male neighbor found his way into my bedroom and was removing the covers off of my bed to get into the bed with me, and I had to physically remove him from the bedroom,” Shannon said.

Her immediate roommate at the time slept through the whole encounter.

Shannon said she went to bed after removing the male from her room and called her boyfriend and mom the next morning to tell them what happened. Shannon said her mom told her to talk to her resident assistant.

Shannon said she then told her immediate roommate what had happened during the night and her roommate felt “extremely violated.” The two went to find an RA to report the incident.

When the two women first went to the RA’s door, there was a note stating that the RA was on an Associated Students of California Lutheran University Senate retreat. Shannon said she and her immediate roommate returned later in the day and told the RA their story. Shannon said the RA told them to wait as she had to deal with something, which according to Shannon turned out to be drugs in the accused student’s room.

“So, she took priority to deal with the drugs over the sexual assault. Which part of me is like OK, she wants the evidence there … but like … call another RA,” Shannon said. “It was kind of like ‘we’ll talk later.’”

When she did report to her RA, Shannon said it was 7 or 8 p.m. that Sunday.

According to Cal Lutheran’s Title IX website “The University strongly recommends that a survivor of sexual assault report the incident in a timely manner. Time is a critical factor for evidence collection (for legal purposes) and preservation.”

Shannon then decided to speak to Campus Safety. She said her RA made her uncomfortable prior to speaking with Campus Safety by telling her that they might ask her questions such as “what were you wearing?” Her RA offered to come with her to meet with Campus Safety.

“So, she had put into my mind that these guys were like gonna blame me … they aren’t going to believe me,” Shannon said.

Shannon said she met with Campus Safety in a “closet” in South Hall with her RA in attendance. Shannon said the meeting was not what the RA had “played it up to be.”

“When I look back at what happened I’m like ‘that was weird.’ I don’t know if [the RA] was doing that just so she could be in the conversation and know what was said. I don’t know. But like it was strange,” Shannon said.

Shannon said Campus Safety asked her what she wanted to do moving forward, and she decided she wanted a restraining order against the accused student. Shannon said the RA then told her she could not get a restraining order unless all her roommates agreed, and informed her she would have to speak with her roommates in a mediation about the order. The mediation began after 10 p.m.

The mediation lasted until midnight, and after two of her roommates told her they did not want to get involved in the process of a restraining order, Shannon said she “lost all hope.” Looking back at the incident she said she “should have known better” as her dad is in law enforcement.

Cal Lutheran’s 2019 security report states that when a report of sexual misconduct is made to the university under Title IX policy, the reporting party will be provided written information on “Where applicable, the rights of the reporting party and the institution’s responsibilities for orders of protection, ‘no-contact’ orders, restraining orders, or similar lawful orders.”

“I wish I would have [gotten a] restraining order. I wish that would have been an option for me. Like, in my mind, it wasn’t an option for me because my roommate said ‘no,’” Shannon said.

Attorney Joseph Lento said that he does not see why it would be the case for anyone to need a roommate’s permission to get a restraining order.

Shannon said about a week after the incident and the filing of a Title IX report, she was contacted by her Title IX investigator Salma Loo, who was assistant director of Residence Life and Student Conduct at the time. Shannon and her immediate roommate told Loo the full story.

“I hadn’t cried about it until I talked to Salma [Loo],” Shannon said. “When I was talking to a Title IX [investigator], I realized how bad this could have gone, how bad it is, like, all of it. That’s when I finally realized what exactly had happened to me.”

A no-contact order was then issued between the accused student and Shannon on Sept. 18, 2016. According to Cal Lutheran’s 2019 annual security report, no-contact orders may be requested between students when a student “has engaged in or threatens to engage in stalking, threatening, harassing or other improper behavior that presents a danger to the welfare of the complaining student or others.”

Shannon said the accused student broke that no-contact order by slipping a note under Shannon’s door, apologizing and saying he got kicked off the football team because of it. At the time he lived next door to Shannon. Shannon reported the incident to her RA and was then told in an email from Paul that the accused student was moved to Grace Hall after breaking the no-contact order.

Shannon said she received an email from Loo regarding the Title IX investigation stating that the accused student was found at fault. However, Shannon said since some of her roommates would not be interviewed, the email said they could only “assume he’s responsible.”

“I was relieved that they found him responsible but…the tone was just different,” Shannon said.

Shannon said she heard rumors two weeks after the no-contact order was issued that the alleged perpetrator was no longer a student following a break-in to another dorm room. She received an email from Loo several weeks later informing her that the accused party no longer attended the school. This invalidated her no-contact order, Shannon said.

An official restraining order would have been filed with the Ventura County Sheriff’s Department. The Ventura County Sheriff’s Office website defines a restraining order as “a court order that helps protect people from abuse or harassment.” Civil restraining orders are “valid anywhere in the United States.”

“I wish it wasn’t so exhausting. I was exhausted dealing with it and it was one of those things where I was fighting so much with my roommates over it,” Shannon said. “I wish someone would have just stepped in and been like, ‘Can we like, talk about what actually happened?’”

Though this incident happened three years ago, Shannon said she remembers it well. She said she still has issues with strangers being in her apartment because of it, but now uses it as a lesson to her Krav Maga students.

“I teach frequent women’s specific self-defense seminars, and I speak a lot about my experience because I think it is important to prove I am a martial artist who’s been put to the test and I passed the test,” Shannon said. “I can tell the story because I speak about it so much.”

Brenda

Another Cal Lutheran student said she contacted Residence Life regarding verbal abuse by a male student athlete in fall 2018. The female student will be referred to by the pseudonym Brenda, as she feared retaliation in her case.

Brenda said the behavior was initially aimed at her boyfriend at the time, who lived with the alleged perpetrator, but that she started having personal problems with the alleged perpetrator when he came into her room with his friends late at night to confront her about an argument he had with her then-boyfriend.

“He pushed the door open so hard and he just came in with ‘you bitch,’ like super loud. My roommate was, like she started crying, my other roommate took off and the other one locked herself in the room,” Brenda said.

Brenda said he came into the room with about four or five other male students who were all intoxicated. Brenda said he proceeded to threaten her “in a very specific way” and yelled at her about her then-boyfriend’s behavior, telling her she needed to “make sure” he changed his habits.

Brenda said she then contacted RAs in her hall, who told Brenda’s then-boyfriend that he should sleep in his car that night to avoid being around his roommate. Later that night it was discovered that all the groceries belonging to her then-boyfriend had been removed from the shared fridge and put on his bed. Brenda said the Graduate Resident Assistant then got involved.

Brenda said the RAs told her they put the incidents in a report. However, Brenda said she did not hear anything more about the situation from her RAs or Residence Life for over a week after the incident.

Therefore, a week after the alleged perpetrator came into her room, Brenda said she decided to reach out to Residence Life herself. She said she scheduled a meeting because she wanted a no-contact order.

Brenda said she first spoke to Caitlin Hodges, who at the time was senior coordinator for Residence Life and Student Conduct. Brenda said Hodges was “really understanding and she was really nice about it.” Later, Brenda said she spoke to Chris Paul, director of Residence Life and Student Conduct and deputy Title IX coordinator.

Brenda said when she spoke to Paul, she felt discouraged from making claims against the male student, and said Paul pointed out that the alleged perpetrator was a student athlete. She said she felt like Paul questioned whether she was telling the truth. However, she said she was able to obtain a no-contact order. The no-contact order was put in place on Nov. 2, 2018, according to the order.

Brenda and her then-boyfriend moved halls the following semester. Brenda said she noticed the alleged perpetrator coming into her new hall more and more frequently, and one day she said she heard knocking on the door and saw the alleged perpetrator and one of his friends standing outside, despite the no-contact order.

“I just broke down in the bathroom, full on started crying, texted all my roommates because they didn’t know what was going on,” Brenda said.

Brenda said none of her roommates were home when he knocked, and she texted them to tell them not to let him in.

After the incident, Brenda said she emailed Residence Life about what had happened, and scheduled a meeting for the following day. Brenda said because it could not be proven that the alleged perpetrator actually knocked, no further action was taken.

Brenda said in her meeting with Residence Life she again felt like she was not being believed, and was referred to Counseling and Psychological Services, which made her feel “horrible.”

Brenda said she then went straight to CAPS and told them everything that happened.

“CAPS was like ‘you’re OK. This doesn’t sound like something that you started. No, you’re not crazy… it sounds like you’re being victim-blamed,’” Brenda said.

Brenda said CAPS then recommended that she contact Campus Safety with her situation.

“[Campus Safety] called it stalker behavior, and they put in a report, and then I didn’t hear anything for like three weeks,” Brenda said.

According to the annual security report, there were three incidents of on-campus stalking in 2018, including one incident in a residential facility. While stalking violates Title IX, to Brenda’s knowledge, no Title IX report was ever filed.

Brenda said she was then called in by Campus Safety and interviewed about what happened. However, once again she felt she was not being believed. She was informed the alleged perpetrator had written a letter saying he was afraid of Brenda.

“I just couldn’t take it seriously. I was like, ‘you’re kidding me’,” Brenda said.

Brenda said Campus Safety then told her they would check security footage, because the alleged perpetrator had told them Brenda followed him to the mailroom one day. Brenda said Campus Safety told her they were going to call her back if they found out that she was not telling the truth, but Brenda never got a call back.

Brenda said Campus Safety and Residence Life then made it so that the alleged perpetrator could not access her new residence hall, and she could not access his. Brenda said they also told her they would not be living in the same residence hall at Cal Lutheran in the future.

Brenda continues to live on campus and said the situation has since improved.

“It has calmed down since my ex did drop out, he no longer is a student here,” Brenda said. “I’m hoping it stays this way. I mean, people are going to talk about the situation no matter what.”

Brenda said she heard rumors at the beginning of this school year that an RA was discussing her situation with other students, and brought this concern to Salma Loo, who is currently the Campus Awareness, Referral, and Education case manager. Loo replied in a Sept. 4 email saying that “an RA should never be sharing information like that with anyone who doesn’t have an educational need to know” and offered to refer the concern to Residence Life.

Brenda said she is grateful for Rabbi Belle Michael and the CAPS counselor she talked to for helping her through the situation.

“I think I would eventually just transfer schools, if it kept up, which I did get very close to. I was looking into other schools during second semester,” Brenda said.

Brenda said if anything similar happened again, she would not go through the school, but do what CAPS recommended and go to the police.

Reporting and Title IX at Cal Lutheran

In April 2015, the U.S. Department of Education clarified the role of Title IX coordinators in the “Dear Colleague Letter on Title IX Coordinators.”

“Your Title IX coordinator plays an essential role in helping you ensure that every person affected by the operations of your educational institution—including students, their parents or guardians, employees, and applicants for admission and employment—is aware of the legal rights Title IX affords and that your institution and its officials comply with their legal obligations under Title IX. To be effective, a Title IX coordinator must have the full support of your institution,” Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights Catherine Lhamon wrote in the letter.

There are two Title IX coordinators at Cal Lutheran, and both hold multiple positions on campus. Deputy Title IX Coordinator Chris Paul is also the assistant dean of students and director of Residence Life. Title IX Coordinator Jim McHugh is also the associate vice president for athletic affairs, which according to clusports.com means “he is responsible for the overall leadership of CLU Athletics, Athletic Facilities, Athletic-related fundraising, Athletic-related programming, student-athlete recruitment, and Athletics Branding and Sports information.”

In the three cases discussed in this article, the women said the accused students were male athletes.

A 2018 study found that college athletes were three times more likely to be accused of sexual misconduct or domestic violence, based on data from 32 Power 5 schools, according to ESPN.

“When designating a Title IX coordinator, a recipient should be careful to avoid designating an employee whose other job responsibilities may create a conflict of interest. For example, designating a disciplinary board member, general counsel, dean of students, superintendent, principal, or athletics director as the Title IX coordinator may pose a conflict of interest,” Lhamon said.

Attorney Joseph Lento said that while Cal Lutheran is a small school that may have limited personnel for Title IX cases, it is not small enough where alternatives avoiding possible conflicts of interest could not be found.

“When the job is not specific, when [the coordinators] have other responsibilities, it could definitely create a couple of issues, one being conflict. Another being not giving the necessary attention or not having enough necessary focus on what needs to take place especially in light of what is at stake for everybody involved,” Lento said.

Some schools such as Pepperdine have a dedicated Title IX coordinator; however, it is not uncommon for small schools to have coordinators with multiple roles. Chapman University’s lead Title IX coordinator is also the associate vice president for student affairs and senior associate dean of students.

“At schools that really try to say, ‘avoid all issues’, if that’s possible, I mean they would have a dedicated Title IX coordinator, that’s all they do… They are not serving other roles at the university,” Lento said.

Lento said Cal Lutheran’s Title IX policy was “limited in terms of the information that’s available… a little less than some school’s would have.”

Pepperdine University has a webpage with 14 sections designated to Sexual Misconduct, including an outline of the appeal process. Chapman has a 30-page sexual misconduct policy, while Cal Lutheran has a 12-page “Title IX and Clery Amendments Policy.”

Cal Lutheran’s 2019 annual security report, governed by the Clery Act, reported three cases of rape, three cases of fondling and three cases of stalking in 2018.

However, Title IX matters are thought to go severely under-reported, with a survey by the Association of American Universities finding that only about 28% of the most serious nonconsensual sexual encounters are reported.

“Any victims of sexual assault are hesitant to file official reports, perhaps worried that they will not be believed, concerned about the investigative and hearing processes, and fearful about scrutiny, stigma, and possible retaliation, but college-age females historically are even less likely than non-students to report rape and sexual assault to the police,” according to the American Bar Association.

According to a 2019 survey by the AAU, about one in four female undergraduate students report experiencing nonconsensual sexual contact at least once during college. One in 10 undergraduate women report experiencing stalking.

Each of these women have a different story to tell.

Editor’s note:

This article began in September 2019 when members of The Echo staff became aware of individuals’ concerns with the university’s handling Title IX-related matters. It should be noted that because of Cal Lutheran’s small enrollment, some of our editors have personal connections with individuals mentioned in this article; however, involvement with reporting for anyone with a prior relationship was minimized. This article was reviewed by two media law experts including Sharon Docter, a professor of communication at Cal Lutheran. We encourage anyone with feedback or additional information related to this article’s contents to contact us at echo@callutheran.edu.