Immigration researchers lift fact over rhetoric

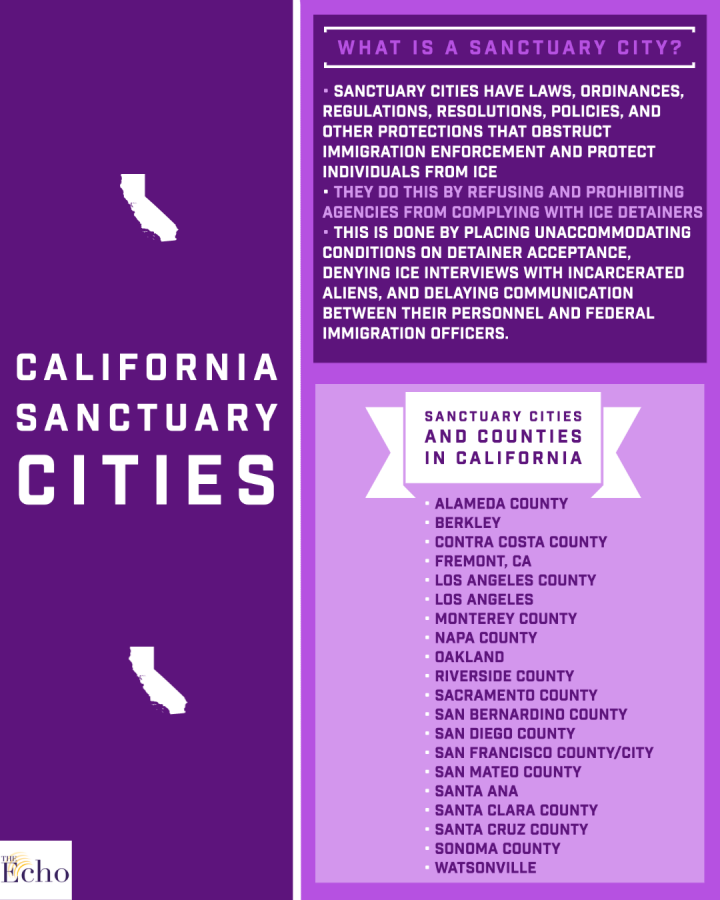

Graphic by Serena Zuniga, Multimedia Editor

The authors of Sanctuary Cities: The Politics of Refuge, led a discussion for California Lutheran University about the history and role of sanctuary cities in the U.S. via Zoom on Sept. 30.

October 6, 2020

On Sept. 30, the authors of Sanctuary Cities: The Politics of Refuge led a Zoom discussion for California Lutheran University about the history and role of U.S. sanctuary cities.

During the discussion, which was organized by the Center for Equality and Justice, authors Benjamin Gonzalez O’Brien and Loren Collingwood addressed how declarations of sanctuary cities are often an effort to combat the rise of anti-immigration policy.

These policies have led to record numbers of deportations for people who crossed the border illegally under the Trump administration.

The authors said sanctuary cities offer people refuge from local police forces by restricting the discussions police can have with citizens based on immigration status and limiting the disclosure of that status with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

“Those departments are going to be using at least some of their resources on federal law,” Collingwood said. “You’re effectively bringing in local sheriff’s departments and police departments into a federal policy arena.”

The presentation explained that the concept of a sanctuary city was born in the 1980s under the Reagan administration, as churches in Tucson, Arizona and other cities provided refuge for Central American immigrants, who sought refuge in the U.S. from violence and poverty.

According to the authors, the concept began to spread from city to city over time, especially with the immigration policies of former President George W. Bush, who created ICE.

With the election of President Donald Trump, even more of these sanctuary cities began to pop up to combat the spike in deportations and the empowerment of ICE to create detention centers and act in a militaristic fashion, Collingwood said.

“There had been an incident in San Francisco … Trump used it as a kicking off point for his campaign,” Collingwood said. “Everything he was saying, it was like all anecdotal.”

The authors discussed the murder of Kate Steinle in 2015 by a man who was in the country illegally, which helped to fuel the anti-immigration narrative.

Trump used this violence as an example of what he said was an immigration-fueled uptick in crime.

“Immigrants don’t commit crimes at a higher rate than native-born Americans,” Gonzalez O’Brien said. “They actually commit crimes at a far lower rate.”

A study, published by libertarian research organization Cato Institute in February 2018, found that individuals born in the U.S. were more likely to be convicted of a crime than illegal or legal immigrants.

Cynthia Duarte, director of the Center for Equality and Justice, who helped organize the event, said despite the statistics, Trump’s “messaging of that is highly effective politically, and so the evidence almost doesn’t matter… it’s [how] anti-sanctuary movements are framed and shows how little they’re based on evidence.”

Trump later used this narrative to fuel both his expansion of ICE and the militarization of the border, Gonzalez O’Brien said. In addition, Trump brought people who were allegedly victims of crimes committed by undocumented immigrants on his campaign tours in 2015 and 2016.

“It is essentially rhetoric that has been used for as long as this nation has existed, to target non-white communities, to paint them as threats to white communities, so that they can be treated as second class citizens, or to be treated as second class people,” Gonzalez O’Brien said.

Collingwood and Gonzalez O’Brien’s book began with research dating back to the mid 2010s, including an article published in 2017.

The authors said their research found that sanctuary cities tended to have larger amounts of 911 calls by Latino communities and more Latinos serving on police forces.

“In immigrant communities they believe that they potentially face deportation because they are asked about their immigration status when they interact with police,” Gonzalez O’Brien said. “This can … drive down crime reporting, and this can also drive down cooperation.”

Their research also found was that 75% of ICE detainees are held in private prisons, and these prisons are publicly traded on the U.S. stock market, Gonzalez O’Brien said.

“A lot of these very anti-immigrant policies that are being promoted are being done so that people can people can profit off the detainment of people in basically jail or prison,” Collingwood said. “These are real human beings … it really puts your conscious at a very uncomfortable position.”

The discussion was originally scheduled for March, but was rescheduled as an online discussion after COVID-19 began spreading in the U.S.

“We’ve had anti-sanctuary movement in Ventura County, so it just really fit in terms of our community and the current political climate right now,” Duarte said.