Student workers to sign confidentiality agreement

April 13, 2023

Editor’s note: The Echo editors are considered student workers and are paid through the university. The reporter for this article is a student worker at the university. Some of the reporters and editors are student workers for departments across campus, leaving conflict of interest difficult to avoid. The Echo strives to be objective and as transparent as possible. Given the potential for this confidentiality agreement to impact The Echo’s ability to report on campus happenings, this article started from concerns by the editorial staff about the future of the publication and their ability to report. Additionally, because of this possible impact on The Echo, the reporter did contact a member of the Student Press Law Center, as seen in the article.

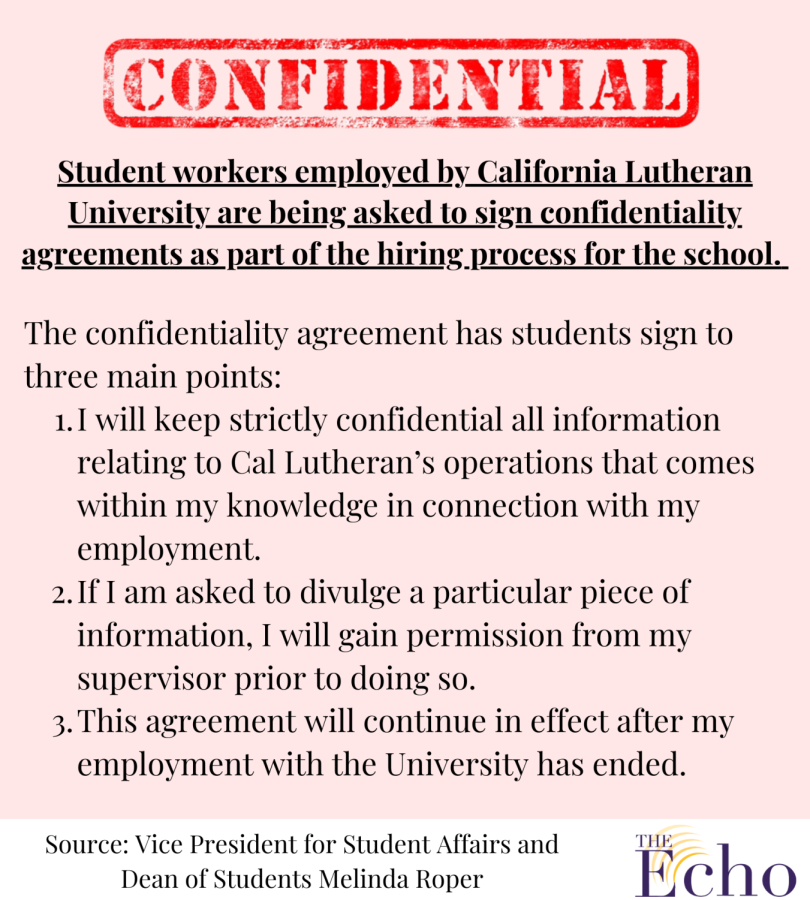

Student workers employed by California Lutheran University are being asked to sign a confidentiality agreement in the near future as part of the hiring process for the school. The confidentiality agreement was drafted by Thomas Knudsen, the former General Counsel of Cal Lutheran, who recently left the university.

“As regards the new confidentiality agreement, many of our student employees at Cal Lutheran work in positions that allow access to sensitive academic, financial and operational information,” Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean of Students Melinda Roper said in an email interview. “Students, staff and faculty trust us to keep such data secure. The new confidentiality agreement impresses upon our student workers the requirement to maintain this professional standard.”

Roper said the confidentiality agreement is a “matter of best practice” and will have students sign for three main points and a warning at the end. The first point is: “I will keep strictly confidential all information relating to California Lutheran’s business or operations that comes within my possession or knowledge in connection with my employment.”

Roper said that the nature of confidential information will likely be different from office to office. She anticipates that supervisors will review expectations under the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act as well as any additional department-specific confidential information requirements.

“Confidential information could be competitive or proprietary information. For example, a student employee in Athletics may learn of a coach’s strategy against another team that we would not want revealed. Another example is student researchers working with faculty should not share intellectual property,” Roper said.

The second point students agree to when they sign is: “If I am asked to divulge a particular piece of information, I will gain permission from my supervisor prior to doing so.”

Roper said the lean toward supervisors is due to the different varieties of students’ jobs and what information they may handle.

“Many students will graduate from Cal Lutheran and work for organizations that seek to protect proprietary information that makes them competitive in the marketplace,” Roper said. “Tech companies, research labs, sports teams, financial institutions are but a few examples of organizations that have employees sign confidentiality agreements related to business or operations.”

The final point is: “This agreement will continue in effect after my employment with the University has ended.”

Even though there is no certain way in which the school will uphold this agreement indefinitely, Roper said there is a possibility of legal ramifications.

“Once students have graduated, the expectation is that confidential information will remain so. If, for example, a graduate released information protected by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, there may be a legal repercussion,” Roper said.

The warning at the bottom says: “I understand that violation of this agreement or release of confidential information may result in disciplinary action through the University’s Student Code of Conduct and/or termination of my employment.”

If a student doesn’t feel comfortable signing the agreement, Roper said, “I would encourage the supervisor to have a conversation with the student to address any questions and/or concerns the student might have. If after that conversation the student still did not want to sign the agreement in the context of a particular position, it may be the case that a different position might be a better fit.”

As it stands now, since it is the middle to the end of the semester, Roper said students will not be required to sign the confidentiality agreement and would not lose their current position if they choose not to.

Roper said, moving forward, the confidentiality agreement will be part of the hiring process for student workers to sign. Student workers make up about 700 students out of 3,615 students, which is just under 20%. Roper said it will not be replacing the Student Employment Personnel Action form.

“The Student Employment Personnel Action form serves as a job application and also contains terms of employment such as performance, attendance and confidentiality,” Roper said. “The new confidentiality agreement is consistent with the confidentiality clause in the Student Employment Personnel Action form.”

Despite it being a part of the hiring process in future semesters, Executive Director of Career Services Cindy Lewis and Senior Coordinator of Student Employment and Career Counselor Edward Kang weren’t involved in the drafting process of this agreement.

“Our office was given this form by our VP to send to student worker supervisors, but I do not have any background on it. We were not consulted related to the reasoning behind it, or the creation of this document. We were just told that all student workers need to sign it,” Lewis said in an email interview.

Apart from issues that may come from a student’s willingness to sign the confidentiality agreement, Senior Legal Counsel of the Student Press Law Center Mike Hiestand said there are also matters regarding the wording of the agreement, such as the over broadness of the wording and lack of end to the confidentiality agreement, that poses problems, especially with a memo recently sent in February by the National Labor Relations Board.

According to an article entitled Non-Disparagement Clauses Are Retroactively Voided, NLRB’s Top Cop Clarifies, in the memo sent by General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo, it was said, “the decision does, in fact, have ‘retroactive application,’ meaning that already-signed and ‘overly broad’ non-disparagement clauses are no longer considered valid by the NLRB.”

Abruzzo said that confidentiality agreements need to be “narrowly tailored” and be based on a set period of time or risk being considered illegal.

“In the case of confidentiality, the clause must serve to keep proprietary trade information secret ‘for a period of time based on legitimate business justifications may be considered lawful,’ but must not have a ‘chilling effect that precludes employees from assisting others’ or communicating with the media, a union, or other third parties,” Abruzzo said.

There are also concerns about legality when it comes to student workers that are also working in the media. Roper had said that the overlap would depend on the nature and context of the information involved.

Hiestand said that the entire job of student media is to divulge information and any confidentiality agreement would prevent students from doing their jobs. Hiestand said that these types of confidentiality agreements are more than just censorship, they are “gag orders.”

“At a public school, there’s a real question about where those gag orders are lawful… but a complete ban on you being able to talk with the media at a public school is pretty clearly unlawful, but even at a private school, there’s some legal issues raised as to whether or not they can completely ban you from doing that sort of thing,” Hiestand said.

Hiestand said that there would’ve been ways to contest this in a public school thanks to the First Amendment, which bans government censorship, but since Cal Lutheran is a private school and the university’s president isn’t employed by the government, it raises issues.

He said that California does have a law in place, the Leonard law, which states that private schools cannot punish you for engaging in speech at a private school if it would be protected in a public school. Hiestand said there was a problem with how the law was written, in that it is limited to preventing punishment, but doesn’t say anything about preventing censorship.

“This is clearly censorship, the question is whether or not it’s legal censorship. It very well may be legal to have this agreement in place, but it’s not very smart, and it’s not workable in the context of student media,” Hiestand said.

Hiestand said he had particular issues with how the confidentiality agreement sounded “very wishy-washy” and “not very well crafted,” especially in the context of student media, in which students operate under a different set of rules from the general population due to the nature of their jobs.

Moving forward, Heistand said he hopes that the university will look into the agreement once more before student workers have to sign, especially those working in the media.

“I’m hoping that it’s just an oversight, that they really didn’t think it through,” Hiestand said. “That there is this little tiny subset of student workers out there that are also journalists, they didn’t take that into account. Hopefully, they will understand that they need to make some changes here for a purpose, at least for the small subset of student workers.”

The Echo sent Roper questions about how the university would indefinitely prevent student workers from speaking about business or operation matters and did not receive a response to this set of questions.